Rapidus eyes foundry opportunity in AI boom, capacity crunch • The Register

Interview The foundry space is arguably the most complex and competitive it has been in decades as foundry upstarts in the US and Japan look to challenge heavyweights Samsung and TSMC for a piece of the action.

But while Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger aims to leapfrog Samsung as the number two foundry operator, Henri Richard, the newly appointed president and general manager of Japan’s Rapidus Design Solutions, doesn’t believe it’s necessary to challenge TSMC directly to be successful given the current climate.

“I personally believe that the demand is understated,” Richard tells The Register.

The sentiment echoes that of others in the industry, including TSMC, Intel, and OpenAI’s Sam Altman. The latter has reportedly been raising billions to support a network of fabs, datacenters, and power plants to fuel his AI ambitions.

“If you believe that the market is going to move from the previous forecasts of maybe $80 billion dollars at the advanced node, to $150 billion, it doesn’t take a large market share to make Rapidus a great success,” Richard adds.

Rapidus rising

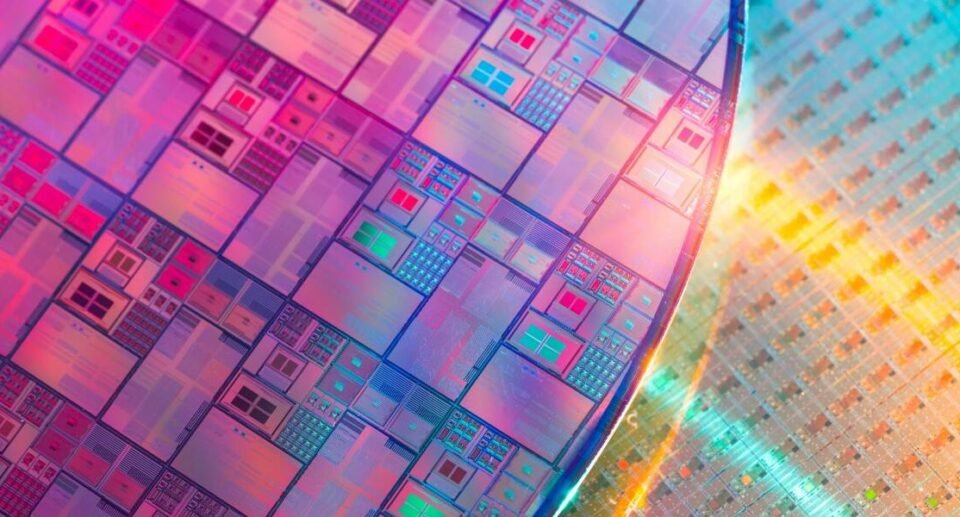

If you’re not familiar with Rapidus, the Japanese foundry upstart is a relatively new player having gotten its start in 2022. It began construction of its IIM-1 plant in Hokkaido in September, which will produce wafers based on an advanced 2nm process node developed in collaboration with IBM.

Armed with $5.9 billion in funding from the Japanese government, Richard says the foundry biz is on track to complete construction later this year and begin installing equipment early next. Following installation, Rapidus will begin the technology transfer of IBMs process tech, being developed in parallel at its research facility in Albany, New York.

“We are on our way to have close to 200 engineers in Albany that are working on the technology and preparing the transfer,” Richard says, adding that pilot production at the Hokkaido plant is set to begin in 2026 followed by volume production in 2027.

Most recently, Rapidus opened an office in Silicon Valley which is focused on sales, business development, marketing, and tech support for potential clients. Early contract wins included Canadian RISC-V chip dev Tenstorrent, which plans to produce its AI accelerator in Rapidus’ fabs.

The competitive landscape

Rapidus aims to establish itself as an alternative source of advanced semiconductor manufacturing. However, achieving this goal may not be so easy as it faces stiff competition from the likes of Samsung, TSMC, and Intel.

One of the company’s biggest challenges relates to timing. TSMC, Samsung, and Intel are slated to being shipping their 2nm process tech in 2025 with volume production expected for 2026. In fact, Intel expects to ship internal chips built using its 20A node — its 2nm equivalent — later this year, followed by its mass market 18A node next year.

This puts Rapidus at least a year behind its competition, a fact Richard acknowledges. However, process tech isn’t the only consideration these days, he argues.

“We might come to an inflection point where, if you just judge a fab, based on when a node is available for mass production, it’s a very partial view of the competitiveness of the offering.”

It’s no secret that performance or efficiency gains from process shrinks, something that we used to take for granted, have become far less impressive as Moore’s Law has slowed. Emerging and maturing technologies like backside power delivery, advanced packaging, and next-gen substrates are expected to play a bigger role in driving performance and efficiency than transistor density in the future.

Richard was hesitant on sharing details on the specific technologies Rapidus is currently exploring beyond its work on process tech with IBM, but says more details would be coming later this year.

Regardless of whether these technologies prove a competitive advantage, he says, capacity constraints alone should be more than enough to guarantee Rapidus’ success, he opines.

An AI friendly fab

From the get-go, Rapidus is focusing on three main markets: serving those building traditional CPUs and GPUs; those designing edge compute; and thirdly, and most importantly, AI chip startups that don’t yet have the volume to make sense for TSMC.

“I think that we are still underestimating the impact and the opportunity that AI represents in terms of semiconductor demand,” Richard says.

“There is a very large and growing number of AI companies that don’t have historical volumes, but represent a pretty good potential for Rapidus,” he adds. “They’re concerned that they would be limited in their ability to be fairly serviced.”

Richard aims to capitalize on these smaller customers by providing additional guidance and support that they might not otherwise get from competing fabs.

Many of these customers, he contends, aren’t actually concerned about getting their hands on the latest process tech.

“I come from an era where everything was, you know, about the semiconductor itself, the transistor, the process, the node, AMD vs Intel, the big battle of the fabs, and all that,” Richard says.

“Frankly, when you talk to those AI companies, semiconductors are kind of a necessary evil. They’re not motivated by the silicon; they’re motivated by what can they do with the silicon.”

Rapidus’ early focus on smaller, indie chipmakers is grounded in the reality that it’s not going to be able to service that many customers until it gains more experience and builds out its capacity.

“When we ramp up the fab, legitimately, we can’t serve more than, what, half a dozen customers to do our job properly at the onset, and then we’ll have more,” Richard says.

A geopolitical and economic play

Another element that shouldn’t be missed here is the ongoing effort by local governments to secure semiconductor supply chains and on-shore production.

The US in particular has raised the alarm bell regarding the concentration of semiconductor production in Taiwan and South Korea. Chief among these concerns is that an invasion of Taiwan by China, which already views the island nation as sovereign territory, could upend the world economy and leave the US at a disadvantage.

These concerns ultimately led to the passage of the US CHIPS Act, which made $53 billion available to fund the construction of domestic chip fabs and research and development. The bill was followed by a €43 billion European equivalent and drove Japan’s investment, which is said to amount to as much as $67 billion in order to bolster its semiconductor capacity.

While TSMC and Samsung were quick to announce US fabs years before the America passed its chips funding, Richard tells The Register that a US fab probably isn’t in the cards, at least not any time soon.

“We’ve never spoken about anything in the US, and I don’t think that’s in the plan. I would say never say never, but it’s so outside of the timeline of relevance,” he says.

Having said that, silicon supply chains and national security can’t be ignored. “It’s a very big component that nobody wants to speak about, too loudly,” Richard says.

“I think we’re in a great position to be seen as a diversification of geographical risk, while being close enough to the US to be seen as a friendly supplier.” ®